Welcome to what may be your first step into your Japanese learning journey. If you’re interested in reading Japanese then knowing the writing scripts is the best first step. Japanese has become somewhat famous due to it’s multiple scripts and difficult writing system, however, do not let that dissuade you from learning. While there are indeed multiple scripts (4 in total including romaji!) and a large number of characters, it’s still possible and quite fun to learn how to use them. Let’s get started with the first set.

The use and rules of Hiragana

ひらがな

Hiragana is the first of 3 Japanese scripts that people typically learn and consists of 46 mora. You may be thinking “What’s a mora?” (Nothin’, what’s a mora with you?…sorry). A mora is a symbol that dictates the smallest unit within language and differs from the letters or a syllables you’re likely familiar with. Because hiragana is made of mora, the sounds in Japanese can be one syllable and yet extend across two or more beats (more on that later).

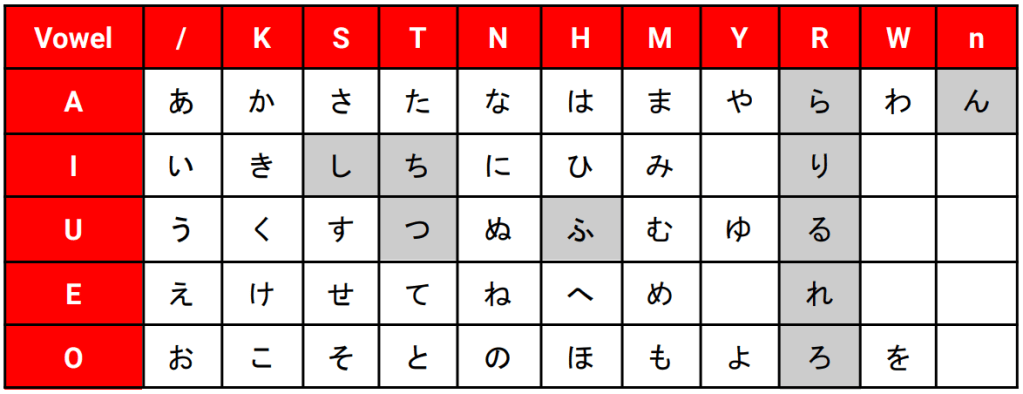

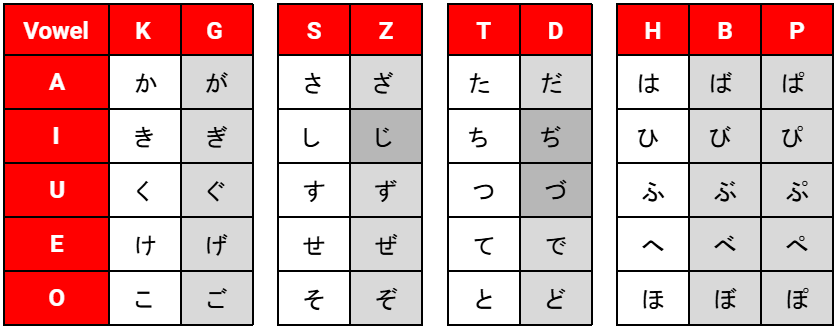

You’ll often see hiragana, also known as kana, laid out in the format of a chart such as the one above. This chart can either be horizontal or vertical and is broken up into 5 lines in one direction (the “vowels”) and 11 lines the other way (the “consonants”). Aside from the first column, marked with a “/”, the sounds of all of the symbols will be made up typically of the consonant of that column followed by the vowel of that row.

E.g す falls in the “S” column and the “U” row so is read as Su

The first column will just be the vowels themselves, so no consonant is used.

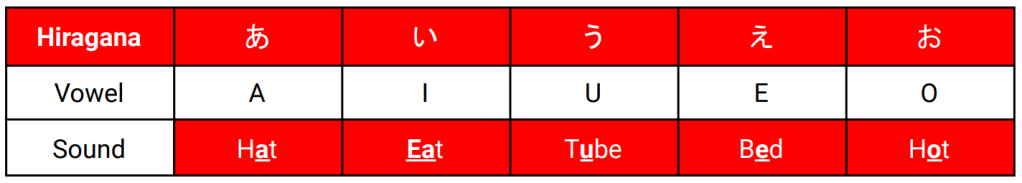

There are some highlighted exceptions which we’ll review shortly, but for the most part it’s as simple as that. One distinct difference between the pronunciations in Japanese compared to English is that the Japanese pronunciations of the 5 vowel sounds is strict and unchanging.

The above chart shows that each of the 5 vowels sounds like the underlined vowel of the example English word. This means that wherever an あ will fall in a word it will always have the same “a” sound we hear in the word “mat”. This differs from English in that the words “car” and “cat” both have an “a” sound and yet they differ significantly. This Japanese pronunciation rule remains consistent for other kana, so a か will have the same “a” ending sound as an あ.

A few exceptions

例外

Referring back to the hiragana chart we saw above, the grey highlighted squares are exceptions to the readings. The highlighted kana below do not follow the rule of one consonant and one vowel or do not match the expected pronunciation.

The first 3 we see actually have two consonants, changing the pronunciation slightly.

し is read like the “Shee” in “Sheep”, ち is read like the “Chee” in “Cheese” and つ is read like the “Tsu” in “Tsunami”. This means that you will not be able to write a “Si”, “Ti” or “Tu” sound in hiragana.

Next, ふ is not read as “Hu” as you would expect. Instead it is read almost like an “F” sound, like a “Phew” or an exasperation of air. Imagine a slightly lighter pronunciation of the “Fu” in “Tofu”.

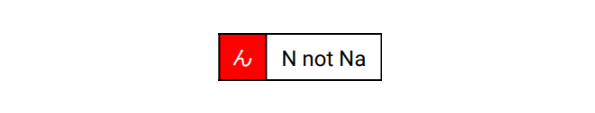

The “n” column is an even weirder exception as it only contains one kana and interestingly enough, although it sits in a vowel row through necessity alone, it doesn’t have a vowel sound. This symbol is simply read as “n”.

Last but not least, you’ll notice that the entire column for the R column is highlighted. This is because the “R” sound doesn’t actually exist in Japanese and instead falls somewhere between an “R”, “L” and a “D”. This is why Japanese native speakers often have difficulty with pronouncing English “L”s and “R”s. In order to replicate this prepare to say a “La” sound, notice where your tongue sits above the back of your front teeth and then try to say a “Ra” from that position. Take the time to familiarise yourself with this. Even try listening to the sound and try to emulate it (Examples here). Once mastered, that “R/L” sound will be used in front of the all the vowels for that line on the chart.

The rhythm of Hiragana

ひらがな の リズム

Let’s revisit the theme of hiragana being made up of mora, rather than letters. Japanese is a rhythmic language, in that each and every single kana will symbolize a sound of equal length. This means that you can count the beats, and therefore the length of a word, by how many kana it’s made up of. For instance, the word “Hiragana”, when written in hiragana, ひらがな, is 4 symbols and is therefore read on 4 beats of equal length.

This rule is true of even the ん kana meaning if a word contains an ん it will still need to be pronounced at an equal length of the other kana. For instance in the word “Nihongo” (にほんご) there are 4 beats again and you’ll hear an audible pause between the “Ho” and the “Go”. “Ni Ho N Go”.

Another interesting aspect of the overall pronunciation of Japanese is that there is significantly less stress emphasis compared to English. We put emphasis on certain words and sentences, such as in the word “English” on the “Eng” sound. Japanese doesn’t tend to do this. As a rule all sounds are stressed equally and the tone remains stable across all speech (For all of you wondering about pitch accent, we’ll look at that quite a bit further down the line…)

Modifying the kana: Dakuten and Han-Dakuten

濁点/半濁点

As stated before, there are 46 hiragana in total. There are however many ways in which the pronunciation of these kana can be modified. There are 4 ways that we’ll review here and the first of those is Dakuten. Dakuten are a diacritic, which is a fancy way of saying they soften the sound of the kana they are marking. Adding a dakuten to a kana is as simple as adding two small dashes to the top right of that character. Han-dakuten (literally a half dakuten) can also be added in the same way but will be shown as a small circle rather than the dashes.

You’ll be glad to know that not all kana can have a dakuten added, above you can see the unhighlighted, original kana columns and the highlighted changes (again with a few small exceptions). Only the “K”s, “S”s, “T”s and “H”s can be modified by dakuten. The “H” column can also be modified by a han-dakuten, resulting in two modified sounds per kana.

The softening of the kana’s sound will only affect the consonant at the start of each kana, the vowel will sound exactly the same. The best way to think about this is to consider how hard the “C/K” sound is at the start of the word “car” and notice the difference when changed to a “G”.

Again, there are some slight exceptions that I’ve highlighted in the darker grey. These are akin to the first 3 exceptions from the above list under “A few exceptions”. While the じ kana is quite common the other two are seen less frequently but are prevalent in compound words and kanji so don’t forget to make a mental note.

Modifying the kana: Compound kana

拗音

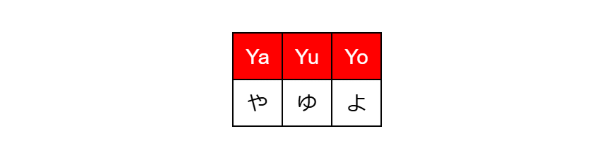

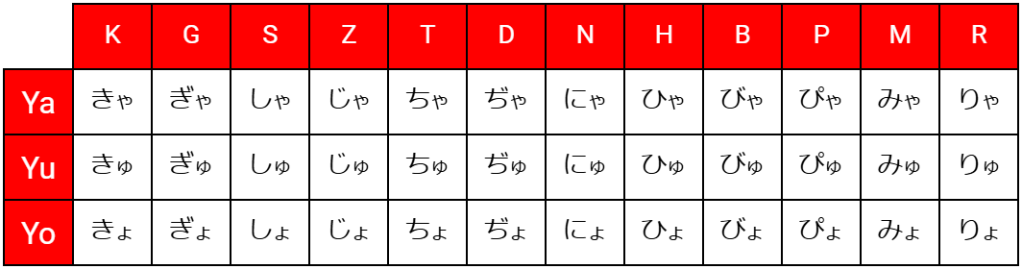

The next way to modify kana is actually to combine them together, making what’s known as “You-on” or “twisted sounds”. Luckily not all kana can be combined, only い sound kana (Such as き, し and み etc.) can be modified in this way.

In order to do so simply pair the kana with one of the above 3 kana from the “Y” line of the chart, making the second kana noticeably smaller to indicate it’s being used to make a compound kana. In total there are 36 compound hiragana, see them in the table below:

Don’t forget about the dakuten exceptions above. じゃ would be read as “Jya” not “Zya”

There are a few important things to note with compound kana. Firstly that, while they are made up of two kana together, they only take up one beat. This means that a word like “Ninja”, written in hiragana as にんじゃ, would take up 3 beats, not 4.

Next, as you can notice in the word にんじゃ, depending on fonts, handwriting or other factors, the size between the first kana and the や, ゆ or よ may not be that different. Remain diligent when learning and reading words and over time you’ll build your familiarity and be able to tell your compound kana and regular kana apart.

Modifying the kana: Small つ (aka the glottal stop)

促音

Following the trend of using slightly smaller kana, the next modification is the small つ. The small つ, also know as a “Sokuon”, isn’t read like it’s larger counterpart and actually doesn’t technically have it’s own sound at all. The small つ creates what’s known as a glottal stop between two other sounds. If you’re an English speaker you may not be familiar with the description of this but you’ve definitely heard people say “uh oh” before.

This little pause between “uh oh” is used in much the same way in Japanese. Simply read the kana before the small つ, pause for one beat and then read the next kana after the つ. You’ll find that this puts a bit of an emphasis or firmness on the kana after the pause.

An example of this would be the Japanese word for “Journal”, にっき. This word is 3 beats, one for each kana and one for the small つ itself. It’s worth noting as well that when you write words with the small つ in romaji (Japanese in Latin characters) you write the consonant after the pause twice, so にっき would be “nikki”

Modifying the kana: Extended vowel sounds

長音

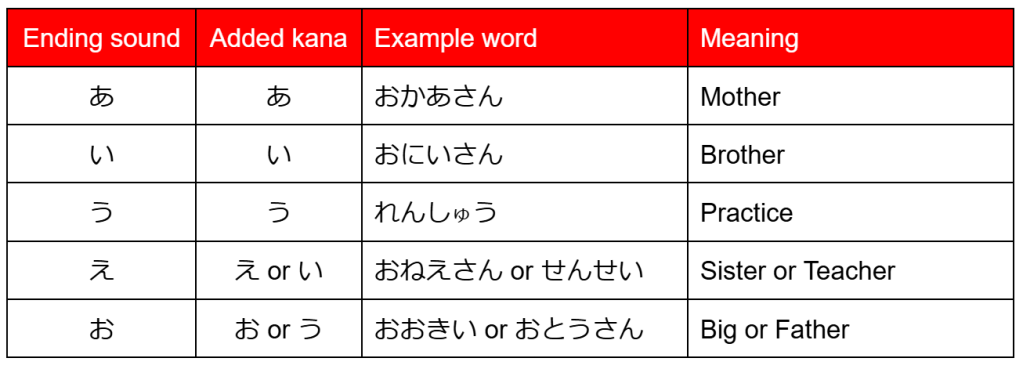

Lastly for hiragana modifications we have extended vowels sounds, also known fittingly as “Chou-on” which is made from the words “long sound”. These are nice and simple as they are essentially just additions of the vowels to a kana of the same ending sound. This makes the sound extend for two beats, maintaining the previous pronunciation.

For instance, taking the か and extending it by adding あ in the word おかあさん, meaning mother. This extension of the ending sound of the previous kana can be done for all of the ending vowels. For instance, あ can be added after any other sounds that end in an あ, い can be added to any other sounds ending in an い and so on.

As always there’s a quirk. You’ll notice in the above table that the examples for え and お sounds can be extended using the い and う sounds respectively as well. These function in the same way as if they were extended by え and お so simply extend the sound as normal. For instance the double length え sound in おねえさん will sound very tsimilar to the end of the word せんせい. You may notice very subtle differences depending on dialect however at this stage the duration and sound of the first kana is more important.

It’s not always the case that a vowel being used after kana will extend it. As a good rule of thumb, if it doesn’t match the ending sound of the kana it follows, it can be read separately and each kana will have it’s own pronunciation and beat. For instance in the word for “World”, せかい, the い sound is distinct from the か before it. However, when words like this are spoken in natural day-to-day conversation you may hear the overall sound become smoother and almost inseparable.

Putting it all together

あわせて いこう

Now that we know all of the ways in which hiragana can be modified within a word we can start to apply and recognise the pronunciations of all the hiragana we will come across.

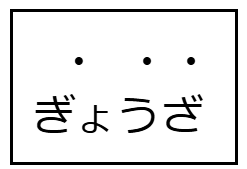

For instance take this common word you may all be familiar with. The word “Gyoza” features 3 of the modifications we’ve seen above. Can you recognise each one? The き and さ have been dakuten’ed to become ぎ and ざ, the ぎ has been turned into a compound kana using a small よ and the お sound has been extended by the う. This again would be 3 beats as the compound kana only counts for one beat. Not too difficult when you know how, huh?

Take a look at the below examples. Try reading each of them, taking particular notice of the length, beats and particular modifications that we’ve learnt above:

This exercise isn’t about learning and memorizing all of the words (although don’t let me stop you if you want to!). It’s more about noticing these interactions of hiragana in the wild. Try vocalizing them and reading them at a slower pace to ensure you are sounding out each kana correctly.

Hiragana is the first and one of the most impactful steps in learning Japanese. From this point on people will think of you as a wizard for simply writing あ from memory. Hiragana plays a large role in Japanese, not only as a way of writing regular words, but also as a guide to pronunciations. When it comes to learning kanji (the dreaded kanji) hiragana often floats above the characters to show you the pronunciations, this is known as Furigana. The beauty of this is that you will be able to pronounce any Japanese words perfectly even before you understand them. Hiragana is also used to make particles, a building block of Japanese grammar. If you can understand hiragana, this new and exciting grammar construct becomes instantly readable, meaning you can focus on the meaning and nuance with not obstruction.

I hope you enjoyed this first step into learning the scripts of the Japanese language. Take the time to commit hiragana to memory. Write it out as many times as your hands can muster, and before long you won’t need to look them up ever again.

From here we’ll move onto the second Japanese script, Katakana. Catch you over there!

Glossary of terms 用語集

Romaji = Japanese written in Roman or Latin characters

Mora = A symbol denoting the smallest unit of a phonetic language. Can show phonetic timings such as sounds shorter than a single syllable.

Phonetic = Relating to pronunciation.

Kana = A word that references a character from either hiragana or katakana, made from the ending of either word.

Stress emphasis = Adding more force or weight to certain syllables within a word or sentence.

Pitch accent = Changing pronunciation from a low to a high pitch to alter the meaning or intonation of a word.

Dakuten/Han-Dakuten = A small double dash added to the top right of certain kana to soften or change the sound.

Diacritic = A glyph added to a letter or to another basic glyph to change the sound of that mora or letter.

Glyph = A purposeful mark that denotes a sound or function in language

You-on = The Japanese name for compound kanji, where small versions of the “Y” line of kana are added after other kana to make a compound kana that last for just one beat.

Sokuon = The Japanese name for the small つ that comes between two other kana to generate a beat of held breath, sounding like a glottal stop.

Glottal stop = A sound where the breath is held mid sound to produce an abrupt pause between sounds, similar to the pause heard between “Uh oh” in English.

Chou-on = The Japanese name for a lengthened sound made by adding kana of the same or similar vowel sound after the first kana.